Do you know how much your retirement will cost? Have you considered how you will pay for it? Do you know how to generate the retirement income you will need?

For many current and future retirees, these can be stressful questions which are often put off and left unanswered for too long.

If you already have a fee-based, fully independent financial adviser then you should talk to them about your specific retirement objectives and set some new goals. Others may prefer to do their own research and make their own plans. Whichever group you fall into, I sincerely hope this guide helps you reach your retirement goals.

What are your retirement goals?

What is your plan for retirement? Indulging a lifelong passion? Travelling? Spending time with your grandchildren? Continuing to work part-time?

In my experience, there are many ways people want to spend their retirement. But from a financial perspective, I’ve found most people want to achieve one (or often more) of the following goals. Before you focus on anything else, it is vital you work out what your goals are for retirement.

Avoid running out of money?

For many, this is their number one goal—and their number one retirement fear. Being forced to turn to your children, or go back to work, during retirement is a source of anxiety for many current and future retirees. Many people think the key to achieving this goal is having only very low-volatility investments, such as government bonds, but as we will discuss later, this may not always be the case. On the other hand, some people truly wish to simply preserve the value of their assets even if their investments will not keep up with inflation.

Maintain or improve lifestyle?

Most people have worked hard for their retirement and want to enjoy it. As such, a common goal for many is to maintain or improve their lifestyle during retirement. The key is to maintain or grow purchasing power over time. This requires income growth to offset the impact of inflation.

Increase wealth?

Some people can easily enjoy the retirement lifestyle of their choosing with no fear of running out of money. For these fortunate individuals, the goal is often to grow their wealth over the long term—typically for a legacy, whether that’s for their children, grandchildren or a charity. Most people with this goal take a growth-oriented approach to their investments.

Spend everything?

Some people want to spend all their money before they die. But this can be a risky proposition as there’s no way to know exactly how long your retirement will last. People who try this need to remember that life expectancies have been trending upwards over time due to medical advancements.

Before you focus on anything else, figure out which of these goals are most important to you. You can’t figure out how to get there if you don’t know where you are going!

How Much Will Retirement Cost?

Once you’ve worked out your goals for retirement, you can start calculating how much your retirement will cost. Four factors to consider are non-discretionary spending, discretionary spending, inflation and your investment time horizon, such as your life expectancy.

Non-discretionary spending

This is the spending you don’t have a lot of control over. There may be some wiggle room, but for the most part, you can’t avoid these costs.

1. Living expenses: Day-to-day, how much does it cost to maintain your lifestyle? You’ll want to consider everything from shopping and fuel to heating bills. If you aren’t planning on relocating in retirement, you probably have a good idea of what these expenses are already.

2. Debt: This can be credit card debt, your mortgage or loans. Anything you owe needs to

be accounted for when identifying your expenses. That’s because you’ll have to keep paying off the main loan and making periodic interest payments.

3. Taxes: Whilst taxes are often lower for retirees, the government still wants its cut. It pays to keep money set aside to settle your tax bill at the end of the year.

Discretionary spending

Once you get past basic living expenses, you have to account for discretionary spending. Discretionary spending depends on your personal situation. For example, you may view your TV package as discretionary, but holidaying as a required, non-discretionary expense. This is just an example, but the message is that if you have a hobby or another expense you can’t imagine living without, you’ll need to include it in your non-discretionary expenses. Here are some of the more common discretionary items in retirees’ budgets:

1. Travel: Many people look forward to travelling in retirement. This could include visiting grandchildren or spending time overseas. If you’ve been thinking about a dream holiday for years, now could be an ideal time to budget for it.

2. Hobbies: Retirement is a great time to restart old hobbies or pick up new ones. Ready to master fly casting or finish researching your family history? Hobbies almost always incur some costs, even if many are small.

3. Luxuries: This is partly subject to your own budget and definition of luxury. But whether you enjoy fine wines or simply meeting friends for coffee most mornings, you’ll need to factor non-essential purchases into your expenses.

4. Children and grandchildren: For many, this last category includes aspects of all the others. Your family could require travel and luxury purchases, and be your favourite hobby all at once. If you need a generous budget to make children and grandchildren a focus in your retirement, you’ll need to think about how much cash flow you’ll need to support it.

Inflation

Inflation is insidious. It decreases purchasing power over time and erodes real savings and investment returns. Investors may fail to realise how much impact inflation can have. Since 1915, inflation has averaged about 4% a year.* If the average inflation rate continues in the future, a person who currently requires £50,000 to cover annual living expenses would need approximately £115,000 in 20 years and around £175,000 in 30 years just to maintain the same purchasing power.

Investment time horizon

Your investment time horizon is a major determinant of your total retirement expenses and perhaps one of the most overlooked factors among today’s retirees. And people can live longer than they might expect. Your investment time horizon can be your life expectancy, the life expectancy of a younger spouse, or a longer or shorter time horizon, depending on your investment objectives.

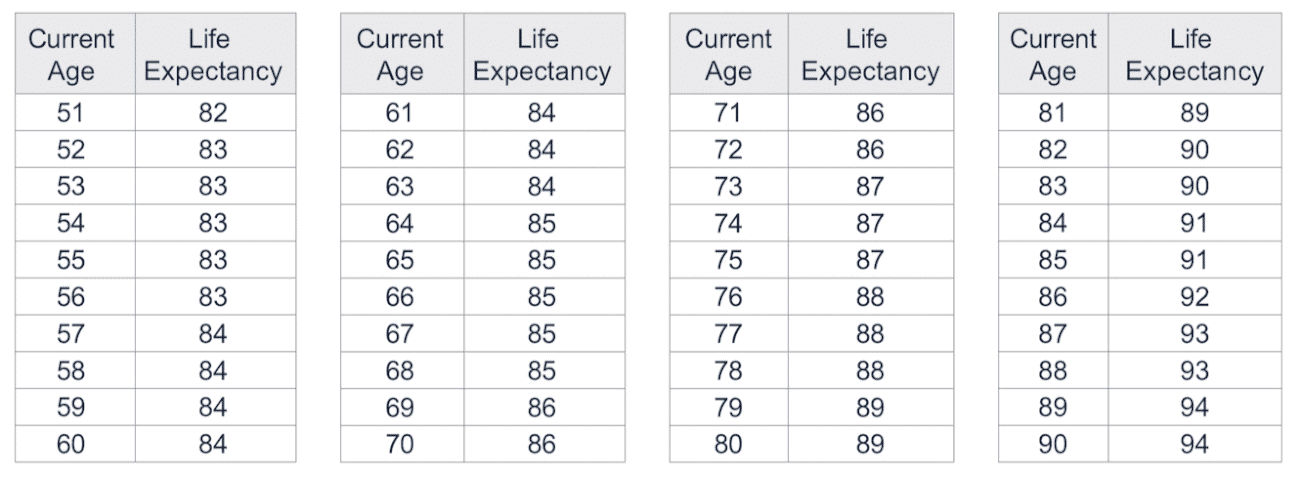

The following table shows total UK life expectancies, based on current age. I believe these projections likely underestimate how long people will actually live given ongoing medical advancements.

And don’t forget these are projections of average life expectancy – planning for the average is not sufficient because about half of people in each bracket are expected to live even longer. Factors such as current health and heredity can also cause individual life expectancies to vary widely, as can your financial “comfort”.

The bottom line? Your investment time horizon may be longer than you realise. So it’s wise to prepare to live a long time and make sure you have enough money to maintain your lifestyle.

Source: UK Office of National Statistics, 2015-2017. Life expectancy rounded to nearest year.

Summary

Your goals, expense needs, investment time horizon, as well as your personal circumstances and attitude to risk, all factor into how you should approach generating income in retirement. Next, let’s examine some techniques you can consider for getting the cash flow you need.

*Source: Global Financial Data, as of 13/2/2019. Based on UK Retail Price Index in GBP from 1915-2018.

How will you pay for retirement?

Once you have an idea of how much your retirement will cost, you can start working out how you’re going to pay for it. I suggest you calculate all the income you generate without relying on your investments. The most common categories of non-investment income are listed below.

Non-investment income

1. Salary: Will you work at all in retirement? If so, you’ll need to estimate how much salary you can expect. To do this, don’t count money you make from a business investment or partnership; just consider direct financial transfers from your employer to you.

2. Pension: If your employer offers a pension, you should determine how much you can expect to receive from it regularly. Will it increase or decrease over time?

3. State pension: The state pension will be available to you when you reach the state pension age. To find out how much you might receive, you can request

a state pension statement from the government’s website. Here’s the LINK

4. Business and real estate: If you maintain an interest in a business or investment property, this could produce non-investment income. When calculating how much to expect, consider these sources of income to be more susceptible to market conditions than the state pension or a guaranteed pension.

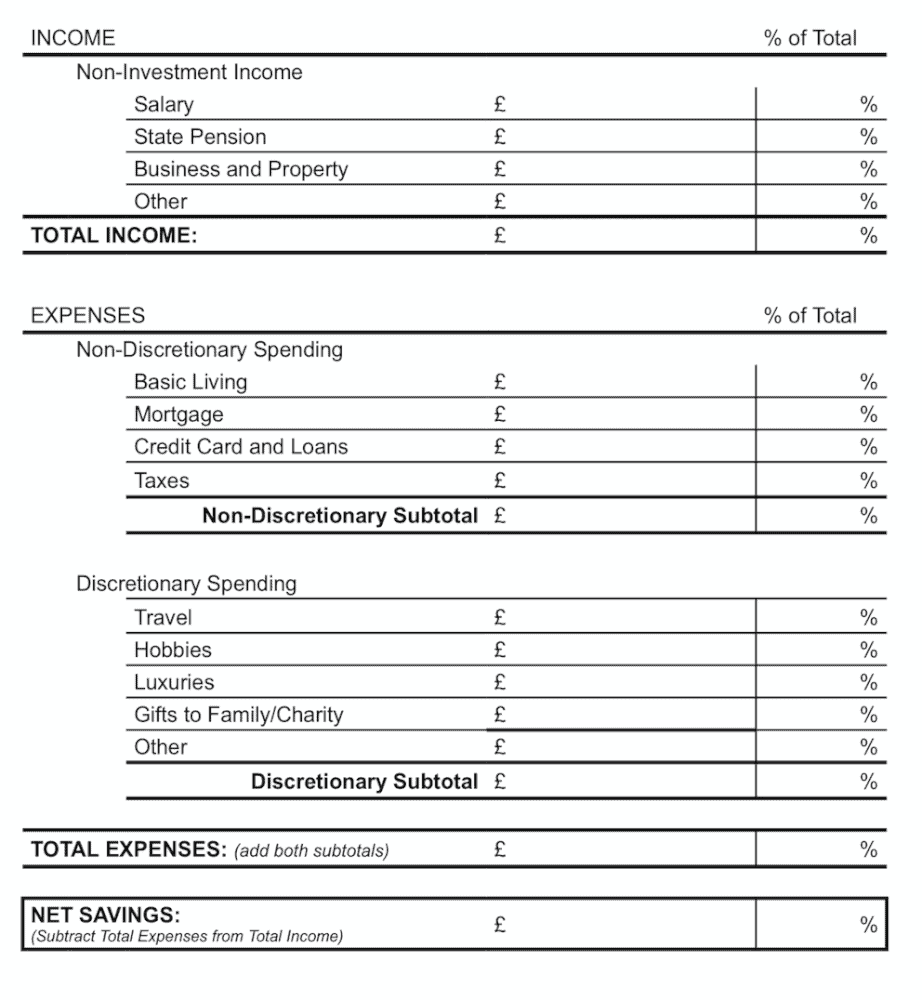

Determining what you need from your portfolio

Now you’ve determined what your expenses are likely to be and how much non-investment income to expect, the worksheet below can help you put it all together.

Using your investments to pay for your retirement

The difference between your total income and your total expenses is your net savings. If this is negative (as it is for many affluent retirees), you may need more cash flow from your investment portfolio to ensure you can cover all of your expenses.

The remainder of this guide focuses mainly on generating cash flow from your portfolio to bridge this gap. But before I explain specific strategies, I’ll discuss some important principles of retirement investing.

Income vs. cash flow

There is a key difference between income and cash flow. Income is money received and cash flow is money withdrawn. For example, dividends and bond coupon payments are considered income – you report them as such on your tax returns. These are two acceptable sources of income, but they are not the only sources of cash flow. Selling an investment also generates cash flow. When you sell an investment, the difference between what you put in and what you take out is considered a capital gain (or loss).

Please note, cash flow withdrawn from your portfolio isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It can be an important component of your overall retirement strategy.

Consider: If you have a portfolio of £1,000,000 growing at 8% a year, and you realise £80,000 in annual gains, this really isn’t any different than a portfolio growing at 4% a year that pays £40,000 in dividends. The total return (capital gains plus dividends) is the same on a pre-tax basis; and, depending on your situation, selling an investment and paying tax on the capital gains may be more tax- efficient than dividend income.

Conclusion: When it comes to paying for your retirement, it could be wise to focus on the total return of your portfolio and cash flow – whether or not it comes from regular income or selling investments.

However, before you can generate income, you’ll need to decide what assets will make up your portfolio.

Asset Allocation

Asset allocation is the single greatest determinant of portfolio returns and likelihood of affording the retirement you want. Essentially, asset allocation is the asset type you decide to invest in. For example, the proportion of equities, fixed interest or cash.

When hearing their asset allocation

could determine if they have enough for

a comfortable retirement, many investors believe they should hold only fixed interest investments, such as bonds.

It is often perceived that bonds are safer than equities because of equities’ higher short- term volatility. However, looking to avoid volatility may result in an investor neglecting their return needs.

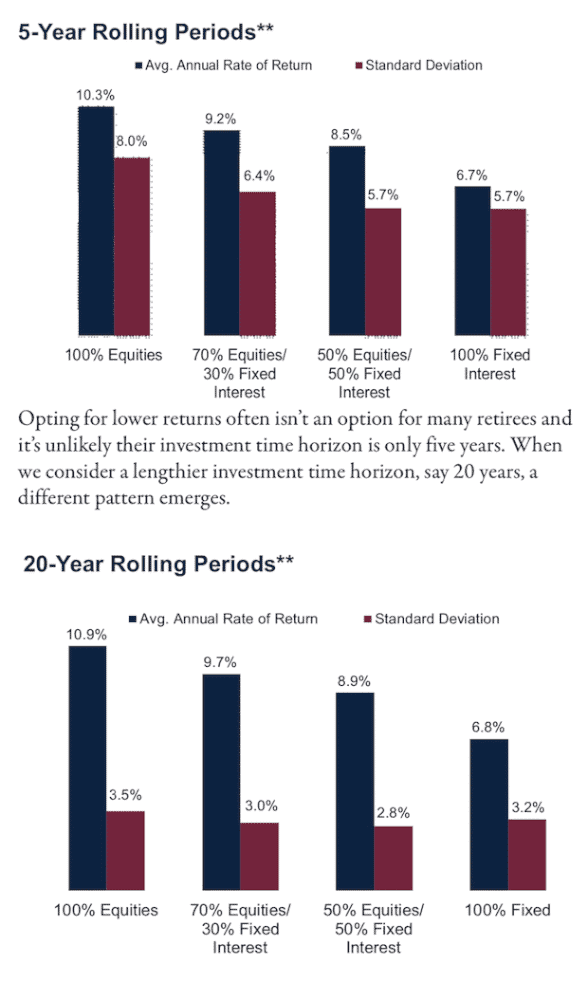

As the following chart illustrates, including more fixed interest in a portfolio delivers less volatility (standard deviation*), but also lower returns over a short five-year period.

*Standard Deviation represents the degree of fluctuations in the historical returns. The risk measure is applied to 5 and 20 year annualised returns in the following charts.

**Source: Global Financial Data, Inc.; as of 31/12/2018. Based on 10.24% annualised GFD’s World Index returns from 1926-2018. GFD’s World Return Index in GBP. The World Return Index is based upon GFD calculations of total returns before 1970. These are estimates by GFD to calculate the values of the World Index before 1970 and are not official values. GFD used specified weightings to calculate total returns for the World Index through 1969 and official daily data from 1970 on.

Over longer time periods, equities actually have lower volatility (standard deviation) than fixed interest. This means if you have a longer investment time horizon and/or higher return needs, you may want to consider a higher proportion of equities for your portfolio. This could be especially true when you factor in withdrawals over the course of your retirement. Of course, you also need to factor in your personal circumstances and attitude to risk (i.e. how comfortable you are taking risk (volatility)).

If you’re taking £50,000 out of a £1,000,000 portfolio every year in withdrawals, you’re more likely to deplete it if your rate of return is too low. You would need a 5% total rate of return every year just to keep your balance the same and that’s before accounting for inflation. If you’re worried about having ‘safe’ investments with low volatility, consider that another risk may be running out of money due to a low rate of return over the lifetime of your investments. Weighing these trade offs is an important consideration.

Next, I’ll address a problem just as serious as returns that are too low: taking withdrawals that are too high.

Risk of high withdrawals

A common assumption is that since equities have historically delivered a roughly 10% annualised average return over the long term,* it must be safe to withdraw 10% from the equity portion of your portfolio without drawing down the original amount you invested.

This isn’t the case. Though equity markets may annualise around 10% over time, returns vary greatly from year to year. Miscalculating withdrawals during market downturns can substantially decrease the probability of maintaining the original invested amount. For example, if your portfolio is down 20% and you take a 10% distribution, you will need around a 39% gain just to return to the initial value. When you consider how damaging years of too-high withdrawals could be, it’s clear how important it is to properly manage your cash- flow expectations and discretionary spending.

Difficult decisions

Investing requires trade-offs, such as more short-term volatility for higher returns or less volatility for lower returns. Another trade-off you may have to consider is between different discretionary purchases. Sometimes you may have multiple expenses that are important to you personally, such as paying for a grandchild’s education or taking a dream holiday with your spouse.

However, to meet your investing goals, you’ll need to be clear about what’s affordable. It’s not advisable to risk depleting your portfolio for non-essential spending. This isn’t to say that helping with university fees or paying for holidays are off limits; rather that they need to be budgeted for realistically in the context of your overall goals, cash-flow needs, return expectations and attitude to risk. Maybe you can do both, one, or possibly neither.

It’s also helpful to be clear with yourself and others about how much you can spend beforehand. Once spending is expected, emotions can come into play and you could face a bigger bill than you’re comfortable with. Any time you’re taking more than 5% from your portfolio, you could be greatly increasing the risk of depleting your assets.

*Source: Global Financial Data, Inc.; as of 13/02/2019. Based on 10.24% annualised GFD’s World Index returns from 1926-2018. GFD’s World Return Index in GBP.

Now it’s time to consider what investments you’ll use to generate income.

Investment income sources

Bond coupons

Bonds can be issued by countries, municipalities, companies or others seeking to borrow money from investors. Bonds are loans. You, the investor, are lending the borrower (such as the company or government) money at a specific interest rate for a specified period. At the end of the specified period, if all goes as planned, the borrower repays you the money you invested. You can also sell the bond on the open market before its expiration date.

There are various more complicated types of bonds, such as callable bonds, zero-coupon bonds and convertibles. These may have a place in your strategy, but familiarity with them isn’t necessary to understand the basics of using bonds to generate income.

Assuming the issuer doesn’t default, your return is predictable and, if you hold the bond until it matures, you’ll get the money you invested back. Certain fixed interest investments, like UK Gilts and other bonds, have very little risk of default. Typically, the lower the default risk, the lower the yield you receive. However, bonds vary widely in credit quality and, correspondingly, yield.

For many investors, the lower volatility of bonds is attractive. The more predictable yield of bonds can be an advantage if you have clear, consistent and time- sensitive cash-flow needs. However, bonds’ lower volatility may mean returns are less over longer time periods. This can pose difficulties for investors who need a higher rate of return to preserve their purchasing power over time. Bonds also face different types of risk than equities, as follows.

There is default risk: the risk that the issuer doesn’t keep their end of the bargain, failing to pay you interest or repay the amount you invested in a timely fashion. But bond risks aren’t limited to default.

Because bond prices can move opposite to the direction of interest rates, a rise in rates will often cause bonds to fall in value. This is commonly called ‘interest rate risk’. It especially affects government bonds, as corporate bonds can be cushioned by other factors, such as improving profits, that governments aren’t subject to. However, all bonds are subject to the impact of changing rates to varying degrees. You might think of bond yields and prices as sitting on opposing ends of a seesaw. Movements in one can drive inverse movements in the other.

Also, since most bonds have fixed interest rates, if inflation rises, the real purchasing power of your cash flow falls. And when inflation rises, interest rates can follow. This means a bondholder can face two risks: falling purchasing power of their current coupons and falling bond prices due to rising rates.

A related risk is reinvestment risk. This is the risk that when your bonds expire and your money is returned, there are no options to reinvest it with similar risk and return expectations as the bonds that just expired. This could mean you have to take on more risk for the same return because bonds are yielding less than when you made your original investment. Bond investors with maturing holdings issued before 2008 may face this risk now.

Dividends

Dividends are attractive. Who wouldn’t want to get paid just for holding equities? But before you opt for a portfolio full of high-dividend equities to try and address your cash-flow needs, it’s wise to dig deeper.

All major categories of equities can cycle in and out of favour, including high-dividend equities. Whether it’s growth or value, small cap or large cap, each category may go through periods where they lead and times that they lag. High-dividend equities are no different. Sometimes they may do well, and sometimes they may not.

You also need to consider what happens to a company’s equities after a dividend is paid. It isn’t free money. Dividend payers’ share price may fall by around the amount of the dividend being paid, all else being equal. After all, the company is giving away a valuable asset – cash.

Nothing about dividend-paying firms makes them inherently better. What’s more, dividends aren’t guaranteed. Firms that pay them can and do cut the dividend—or stop it altogether. For example, in the US, a utility company with a long history of paying dividends stopped for four years whilst its shares fell from the low $30s to around $5 between 2001 and 2002. Banks and other firms also cut their dividends during the 2008 global credit crisis.

As an investor, it is prudent to care about total return. If you’re determined to invest in dividend-payers regardless of market conditions, it could cost you money. You may be better off diversifying and investing in securities that fit into an overarching, cohesive strategy. Remember, the highest after-tax total return should be the goal, regardless of where it comes from.

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with dividends. But it is wise not to make them your sole point of focus.

Next, we’ll see another option for investors who allocate a portion of their assets to equities.

Homegrown dividends

I like to call selectively selling equities for cash flow ‘homegrown dividends.’ It can help you maintain a well-diversified portfolio appropriate for your goals and objectives. It also has the additional benefit of being a flexible, potentially tax-efficient way to generate cash flow.

Tax treatment for long-term capital gains can be cheaper than that for bond interest, which is taxed at your (likely) higher marginal ‘earned’ income tax rate. With dividends, taxation can differ depending on the circumstances. Selling equities can afford you greater flexibility in balancing realised gains and losses. You can sell ‘down’ equities as a tax loss to offset capital gains you might realise, or pare back over-weighted positions – options you may not have if relying on dividends alone for cash flow.

For example, if you have a £1,000,000 portfolio and you take £40,000 a year in monthly distributions of roughly £3,333, it’s a good idea to keep around twice that much cash in your portfolio at all times. Then you aren’t committed to selling a precise number of shares each month and you can be tactical about what you sell and when. But it’s prudent to always be looking to cut back, planning for distributions a month or two beforehand.

Generally, it is possible to get more out of your portfolio from selling equities – if done wisely. And that means you can, if appropriate and consistent with your objectives, needs and attitude to risk, keep more of your money in an asset class that has a higher probability of yielding better longer-term returns.

Whilst seeking total return, you may even have some dividend-paying equities to add additional cash.

However, that decision can be based on whether you think they’re the right equities to hold from a total return standpoint – and you aren’t tied to them just because of the dividend.

Alternative investment income sources

Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs)

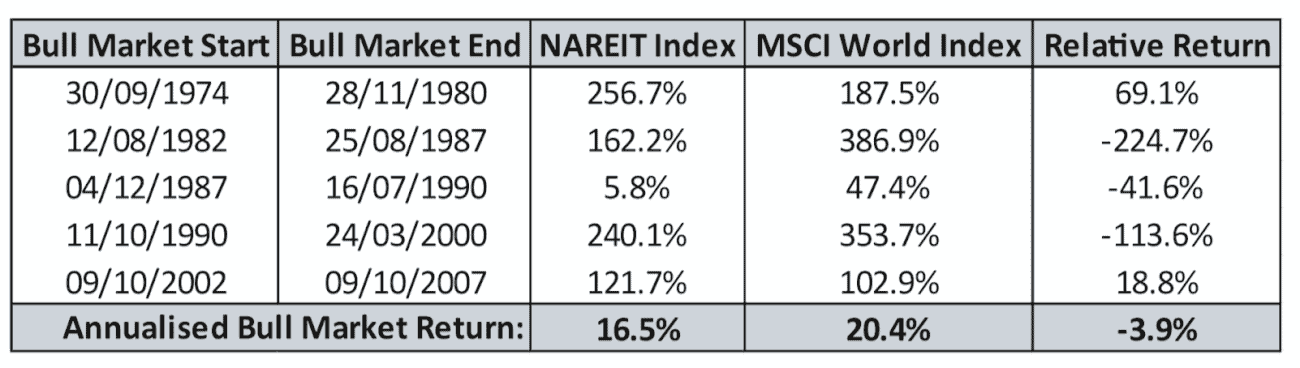

A REIT is a pass-through entity formed to invest in real estate properties. In general, these firms purchase office buildings, retail space, flats, assisted-living or medical facilities, and hotels or holiday resorts.

REITs generate most of their revenues from rental or lease income. They’re required to distribute 90% of their profits to shareholders every year via dividends. They benefit from a favourable tax policy, as qualified REITs are not required to pay tax at the corporate level.

Whilst it may seem great to have such a large share of profits returned to you as an investor, this is also one of the reasons US REITs have often historically underperformed the broader equity market during bull markets. A company that pays out 90% of its profits may be unable to reinvest into its business to grow organically. Consequently, the industry currently comprises smaller companies which can lack the fundamental growth characteristics typically favoured as bull markets mature and organic growth rates broadly decline.

Source: FactSet. Total returns are in GBP, gross of fees. The FTSE NAREIT Index contains all US tax-qualified REITS with more than 50% of total assets in qualifying real estate assets other than mortgages secured by real property that also meet minimum size and liquidity criteria (per FTSE.com). A US REIT index was used for illustrative purposes as REIT indexes for other countries lacked a substantial track record. The MSCI World Index captures large and mid cap representation across 23 Developed Markets countries (per MSCI.com). Relative return is the difference between FTSE NAREIT Index return and the MSCI World Index return.

Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs)

An ISA (for UK investors) provides you with a tax-efficient way to save or invest. As money you withdraw isn’t regarded as ‘income’ for tax purposes, you can take out as much as you like, without risking entering a higher-rate tax band. Conversely, withdrawals from pensions are taxed as income, except for the tax-free allowance element. Retirees may find ISAs useful in various ways, such as using them to meet daily expenses so that they can leave their pensions untouched. Additionally, retirees might use their ISAs as a source of emergency income, for example, when needing to pay for large one-off expenses.

Getting help

Some of the sources of income I’ve covered may have a place in your portfolio, but it can be overwhelming to figure out which is right for you. That’s where a skilled professional adviser can help. I am happy to introduce you to a highly qualified, fee-based independent financial adviser either in the UK or abroad, without obligation. Andrew. Contact me.

How an Independent Financial Adviser (IFA) can help?

Planning

Independent Financial Advisers (IFA’s) can craft a recommended asset allocation strategy based around the goals, investment time horizon and cash-flow needs, as well as your attitude to risk and other personal circumstances, you’ve now defined. Where deemed suitable, IFA’s will provide recommendations that can also include discretionary investment management services that are tailored to your specific needs.

The asset allocation strategy that you’re comfortable with should guide every investment decision. The market isn’t intuitive—in fact, what feels right may be wrong, and what feels wrong may be right. This is why a strategy is so important.

Portfolio management

Portfolio management services are provided by highly trained and experienced IFA’s who will be familiar with your aims and objectives. It is important that your attitude toward risk is regularly assessed and your investments accurately reflect your wishes and circumstances

Investment counselling

The main objective of any decent IFA is to help you reach your goals and keep you educated on and comfortable with the management of your portfolio. A big part of this is helping make sure you understand your strategy and that you stick to it.

Investing involves emotions, and good IFA’s will help you maintain discipline at all times, whether the market is rallying or falling. Think of them as your investment counsellor, with their three main roles being:

- Help you understand what’s going on in your account and why

- Review your investment goals and other circumstances regularly

- Handle your day-to-day needs quickly and smoothly

It is worth noting that most highly personalised discretionary management portfolio services are only available to those with investable assets in excess of £250,000. However, don’t let that put you off if you have a more modest level of savings. Discretionary management investment services cost money – and although they are great from those with larger portfolios, you can still benefit from independent advice from a highly skilled adviser no matter how much money you have.

Statutory notice

Investing in financial markets involves the risk of loss and there is no guarantee that all or any invested capital will be repaid. Past performance neither guarantees nor reliably indicates future performance. The value of investments and the income from them will fluctuate with world financial markets and international currency exchange rates.

Recommended reading:

Interactive Investor (ii) Great British Retirement Survey 2021